By: David Farer

By: David Farer

On Tuesday morning, as I was getting ready to leave my home, a woman’s voice said “Tzeva Adom! Tzeva Adom! Tzeva Adom!” over Sderot’s public speaker system. I had already heard this alarm a few times that morning, and several hundred times since I moved to Sderot. It meant that a rocket fired by Hamas in Gaza would explode somewhere in or near Sderot in about fifteen seconds. I went about my business, turning off my computer and packing my books, as I awaited the explosion. When the inevitable happened, I heard that unmistakable cracking sound

at the tiny fraction of an instant, the KA of the KABOOM! It indicated the Arabs had been lucky this time and hit somebody’s home, instead of their rocket’s landing in a field whose mud muffled the blast. One learns to pick up these subtle differences in kinds of explosion if one lives in Sderot. Less subtle was that my building shuddered, and my windows danced in their frames; I felt the slight shove of the shockwave going through my body. I knew that this Kassam rocket had landed within a few blocks of my home.

I gathered up my books and my notepad and set out to find it. I usually walk along asking people I meet, most of whom point me in the general direction of where the Kassam fell, until I arrive at the bomb-site, but this time the rocket was easy to find. The whirling red lights of ambulances drew my eyes down the alley that opens immediately opposite my building. An old man stood on his porch staring down the alley at the ambulances. I followed his stare until I saw which house had been hit. I walked slowly toward the ambulance’s flashing lights. I noticed myself unconsciously slowing my pace. This is the moment when I always feel fear – fear of what I will see when I get to the house the bomb hit.

Having spent a year opposite the entrance to this alley. I recognized the home and the faces of those who lived in it. The ambulances had been present for a few minutes by the time I arrived where they had parked to take on wounded. As I stood there, the ambulance crew wheeled an old woman wearing a bathrobe to the back of an ambulance. The chair in which she sat had been designed to collapse into a kind of stretcher when pushed up against the rear entrance of an ambulance. The woman herself appeared stunned into passivity. Her face was immobile, but her hands and her body shook as she stared into space. Though conscious, she made no eye-contact with those around her. A younger woman ran up to her yelling, “Ima! Ima!” – “Mother! Mother! in Hebrew. The ambulance drove away with the old woman and some younger people whom I guess were members of her family. Magen David Adom crew-members whom I have interviewed told me that they prefer to evacuate Kassam-victims together with members of their families who are uninjured in ordered that the uninjured will support those who have been hurt.

The house that had been hit stands on the corner of that alley and the street it meets. Police were hanging up marking tape to exclude civilians from walking around and getting in the way of those who had work to do, or of being hurt by any bomb that might be hidden in the home’s rubble. Neighbors, firemen, police, reporters, photographers, even the one or two retarded kids who seem to show up whenever there is a bombing – they all made a busy scene. In a small town like Sderot, people know each other, so the neighborhood folks greeted the police and the other officials who arrived as old friends as well as helpers.

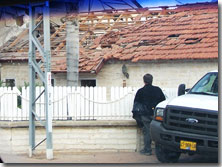

We all stood on the broken glass covering the street and the sidewalks. These rocket attacks all produce huge amounts of glass shards. This particular rocket had landed directly on the roof of the home, sending many of baked clay, Italian-style shingles flying into the alley, the street, and even into the yard of a home across the street – thus accounting for the loud CRACK! I had heard just as the rocket exploded.

A sapper walked into the house to verify that no other bomb was about to explode and kill us all. Somebody else shinnied up an electric pole, probably to turn off the house’s electricity. A young man, whom I assume was a son of that family and a grandson of the old woman who had left in an ambulance, leaned over the fence surrounding his front yard. Newspaper reporters asked him to tell what had happened about fifteen minutes earlier. One of them, evidently English, took notes while an Israeli with him translated the conversation for him. Another Englishman asked this reporter if he had seen the old lady taken out who was shaking “like this”, demonstrating her movements with his own body. The two Britons looked genuinely shocked by what they saw in Sderot.

The young man whom they tried to interview had a look I have seen many times in Sderot on faces of people a short time after they have had a narrow escape. I cannot easily describe him, but he looked calm at first glance. After speaking with him for a few minutes, however I noticed a certain flatness of expression in him, though, both verbal and facial. He spoke in a quiet, almost mechanical manner. This quiet manner is not the same thing as calmness.

As we stood on the sidewalk talking to him over his fence, he told us that he and his family had carried mattresses, the television, and some other things into their family shelter, and that they had been living in it since the recent escalation began. They emerged only to use the toilet and the kitchen. The family had been inside their shelter at the moment when the rocket hit their home. For this reason they are still alive.

I listened to him for a while, and then I crossed the street to say hello to Prosper Peretz, owner of the Peretz Shefa Market on this street, Mivtza Sinai. His shop stood immediately opposite the home that was hit, and he surveyed the scene from the sidewalk in front of his foodstore. I often shopped in his little store, which his parents had founded. They had been among the first Moroccan families to come to Sderot and live in the old pachonim, or tin prefabricated boxes of fifty years ago. His father had opened this shop, and Peretz inherited it. He lives above it with his wife and children, all of whom help run the family business. I asked Peretz if he had been present when the rocket exploded. A calm and soft-spoken man, who spent much of his life in army uniform, he nodded his head. I asked about damage on his side of the street. He pointed to blown-out windows above his shop. Peretz was polite, but evidently not in a communicative mood today.

I walked inside to greet Peretz’s daughter and to buy a chocolate bar. I asked her about her experience of the bombing. She told me she had been upstairs when the rocket hit her neighbor’s home across the street, but that she ran downstairs just in time to see her father taking care of “the one who was wounded.” My eyebrows went up. “What’s that?”, I asked. She told me she ran downstairs and saw her father bandaging a bleeding man who was lying on the sidewalk outside their shop. Prosper Peretz, a man with the calm, humble demeanor of the professional soldier, had told me nothing of that.

I went out to ask him what he did. He smiled slightly and told me that one of the sons of the family whose house had been hit had been walking down the street, either to or from home, when the alarm went off. Hearing the recording, he tried to run into the Peretz Shefa Market, but he did not run fast enough. The man had received two shrapnel wounds, one of which made a gash on his cheek. The second piece of metal opened the artery on the left side of the young man’s neck. Blood being pumped up to his brain was squirting out in bursts, each burst in accordance with the heart beat that sent the blood in the direction of his brain. The young man would clearly have bled to death soon had Peretz not taken action. His daughter walked downstairs to the sidewalk to see her father saving a life. She went into their shop to call an ambulance. This ambulance had left just a minute or two before I arrived, carrying the man whose life Prosper Peretz had saved. “I see”, I said. Peretz told me he was able to do that because of the good training he had received in the army.

“And by the way, why are you wearing a mere undershirt on a cold and rainy day?” “I used my shirt on the guy’s neck.” I pointed to what I now understood to be bloodstains on Peretz’s undershirt, and he just nodded his head – “It happens here.”

I stood there trying to think of a way to express my admiration for someone who had just saved a life, but who had no wish to display that fact, when the alarm sounded. Peretz, bystanders, police, and I went inside his shop. We stood looking at each other for about fifteen seconds until we heard the explosion. It was elsewhere in Sderot – not very close. We walked outside together.

My thoughts on what had happened were interrupted by yet another alarm announcing yet another rocket coming our way. People in front of the bombed house were running inside. Bystanders like me are not allowed into a building just after it has been hit, but in Sderot it is normal for anybody to run into any home when the alarm sounds. I hopped over there and inside the door. I wanted to see how the house looked.

Those of us inside hurried into the indoor shelter in which the family had been sitting when the bomb hit. It looked like an ordinary room, though with no windows, and mattresses instead of beds. After the rocket explodes – again, not close to us – we filed slowly toward the front door, walking through a hallway that opened onto what had recently been a living-room. The roof was gone, so that I could look up and see the sky above us; more of those clay shingles lay scattered about the floor; and dust lay everywhere. This little hallway itself was under half an inch of water. Pipes tend to burst in houses that rockets hit.

I stood around for a while looking at the scene and talking to some people. Prosper Peretz blended into the crowd. A few of his friends showed up to ask him what had happened. He told the story of how he stopped the young man’s bleeding several times, shortening it a little each time, as he became tired of repeating himself. I did my shopping in his store, and I went home.